Gastroparesis is a gastrointestinal disorder that requires serious lifestyle changes and great discipline. People with the disorder have limited food choices and a structure of feeding that must be strictly followed to avoid developing serious complications. Women are often more at risk for gastroparesis, which can be more problematic when they become pregnant.

It is possible to have gastroparesis during pregnancy. However, there is no scientific evidence showing that gastroparesis can place pregnancy at risk. There is also no conclusive evidence showing that gastroparesis is genetically acquired.

This article will explain gastroparesis, its symptoms, factors, and causes, as well as risks and complications. It will also explain how gastroparesis can affect pregnancy and how to manage gastroparesis for pregnant women.

What is Gastroparesis?

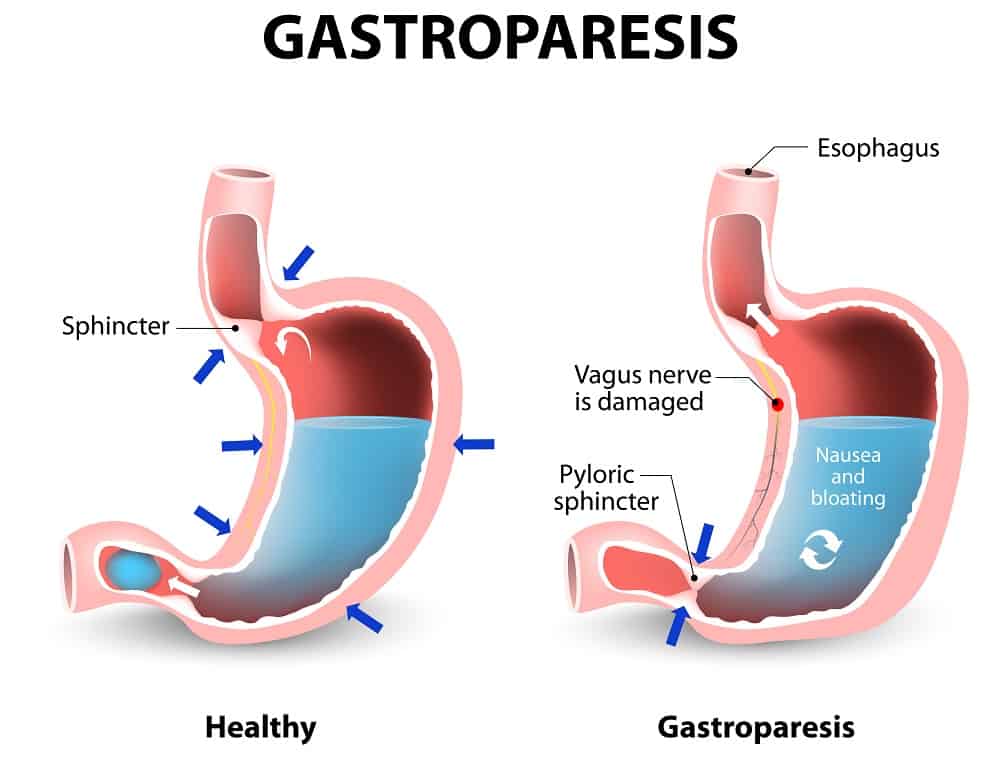

Gastroparesis, also referred to as stomach paralysis, is a gastrointestinal disorder wherein inadequate processing of food materials in the stomach hinders gastric emptying. Normally, the stomach muscles perform spontaneous movement using muscular contraction to churn food and deliver it to the small intestine in a consistent manner to allow the food to mix with the digestive juices found in the small intestine, liver, and pancreas. However, weakness of the muscles of the stomach in gastroparesis prevents the stomach from processing food thoroughly, reducing or stopping motility.

Gastroparesis occurs mostly in women, consisting of almost 80% of cases. Statistics from the National Institute of Health (2018) have also shown that 40 women and 10 men experience gastroparesis in every population of 100,000 people.

Symptoms

Some of the major symptoms of gastroparesis are vomiting, acid reflux, heartburn, bloating, and abdominal pain. It can result in vomiting of undigested food after a meal due to lack of stomach grinding. Some individuals can also vomit even with an empty stomach because of the accumulation of stomach acid.

Possible Causes

Gastroenterologist Dr. Kavin Nanda noted that gastroparesis has several categories: diabetic gastroparesis, idiopathic gastroparesis, and post-surgical gastroparesis.

Diabetes is the most common cause of gastroparesis. It occurs due to damage to the vagus nerve that controls stomach muscle contraction. A damaged vagus nerve cannot send signals to the stomach muscles to process food. This nerve can be impaired as a complication of diabetes.

Idiopathic gastroparesis is the second-most common type of gastroparesis after diabetes with no known cause or factors. Many people who do not have diabetes, have not undergone any surgical operations, and do not have any neurological or endocrine problems are categorized as having idiopathic gastroparesis.

Some people also experience gastroparesis after a surgical operation, mostly on the gastrointestinal tract. This can be caused by an inadvertent disruption of the vagus nerve during operations like fundoplication, heart or lung transplant, or peptic ulcer surgery.

Other causes of gastroparesis involve blood mineral imbalance, specifically potassium, magnesium, and calcium. Hypothyroidism or the lack of production of thyroid hormones is also a possible cause, as well as high glucose within the body.

More serious causes of gastroparesis are viral infection within the GI tract like gastroenteritis, connective tissue diseases like scleroderma, autoimmune GI dysmotility (AGID), Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and amyloidosis. It is also possible for people with anorexia nervosa to temporarily experience gastroparesis until they resume their normal food and liquid intake.

Some medications are also suspected to cause gastroparesis. This can include narcotic pain medication, anti-depressants, and opioid pain relievers.

Gastroparesis has a female predominance, which is attributed partly to reduced gastric contractility because of the hormone progesterone during the luteal phase (Achong et al., 2011) of the menstrual cycle.

Complications

Gastroparesis complications can lead to hospitalization due to dehydration and malnutrition. In some cases, unprocessed food can ferment and lead to bacterial growth in the stomach. Food can also harden inside the stomach and form bezoars that can block passage into the small intestine.

It can also make diabetes symptoms worse as sugar levels may increase abruptly when food is finally able to leave the stomach and enter the small intestine. Gastroparesis makes it harder to maintain optimal blood sugar levels.

Most importantly, gastroparesis symptoms can hinder day-to-day activities and make it difficult to keep up with tasks and responsibilities. People with gastroparesis require effective symptom management planning and lifestyle changes to mitigate its impact on overall life quality.

Risk on Pregnancy

Pregnancy, by itself, is already associated with gastrointestinal neuromuscular dysfunction. But gastroparesis, specifically, is rare during pregnancy. Nevertheless, there have been case reports discussing this condition presenting among pregnant women.

Achong et al. (2011) reported on a case of a 24-year-old, who was pregnant for the first time and had severe gastroparesis, diagnosed at 10 weeks age of gestation. She delivered at 38 weeks gestation via cesarean section for intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and anhydramnios (lack of amniotic fluid). The patient developed preeclampsia (elevated blood pressure) on day 2 postpartum, which resolved spontaneously on day 5 postpartum. The authors concluded that an underlying scleroderma was possible.

Fuglsang & Ovesen (2015), likewise, reported on a case of a 28-year-old, who had type 1 diabetes mellitus and has been trying to conceive for 13 years before finally becoming pregnant. She had been diagnosed with diabetic gastroparesis five years before and was implanted with a gastric neurostimulator, which drastically improved her condition. During her third trimester of pregnancy, symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and constipation required her to have periodical bed rest. At 38 weeks gestation, she had spontaneous labor and uncomplicated vaginal delivery.

People with gastroparesis can have a normal pregnancy and can give birth successfully. However, the experience of gastroparesis for women who are pregnant can differ widely.

Currently, there is no scientific study that shows that gastroparesis can put a woman’s pregnancy at risk. There is also no evidence showing that gastrointestinal disorders like gastroparesis increase the risk of miscarriage.

However, consulting an obstetrician to monitor the status of pregnancy can relieve the stress that can often aggravate the symptoms of gastroparesis. Also, it is good to consult a motility specialist to learn more about proper symptom management that will not put the pregnancy at risk.

Some women with gastroparesis have a gastric neurostimulator which is an implanted device that sends electric impulses to the stomach to facilitate churning and alleviate gastroparesis symptoms. There is currently no established scientific evidence showing the risks of using gastric neurostimulators on pregnancy. There is also no evidence of any complication on pregnancy that occurred due directly to gastric neurostimulators.

While gastroparesis medications, such as erythromycin, are generally accepted as safe during pregnancy, it is still best to prioritize lifestyle changes, mild activities such as yoga, and intake of supplements over conventional medicine to maintain a proper margin of safety during pregnancy.

Is it Genetic?

Idiopathic gastroparesis may be genetic, but genetics alone cannot account for the complex nature of this disorder. If it is not caused by diabetes or surgery, it is likely due to a confluence of a multitude of factors including gut health, gut microbiome, hormones, diet, lifestyle, and genetics.

It can also be a result of pregnancy, given that some women have only begun to experience symptoms of gastroparesis during pregnancy and did not exhibit symptoms afterward. Some women have also experienced symptoms during pregnancy and have continually experienced symptoms even after giving birth.

How to Manage Gastroparesis During and After Pregnancy

Despite the lack of study on gastroparesis and pregnancy, a lot of women have successfully given birth despite having the disorder. They have also been able to take care of their baby while managing the symptoms of the disorder.

It is important to have a comprehensive plan for symptom management and self-care during pregnancy. This will help remove the unnecessary burden and stress of enduring gastroparesis while nourishing the body during pregnancy.

The management for gastroparesis is multifactorial and involves supportive management, pharmacological treatment and interventional therapies. Changes in the diet involve eating small volume of meals that have low fiber and low fat contents. Caffeine and tobacco, which stimulate gastric emptying, should be avoided, as well as fat and chocolate, which reduce the lower esophageal pressure (Achong et al., 2011) and may lead to vomiting.

Artificial nutrition can also help to supply ample nutrients into the bloodstream. Intravenous or parenteral nutrition involves injecting essential nutrients directly into the bloodstream. This can help bypass the stomach for people with severe cases of gastroparesis and widespread motility disorder.

Enteral feeding is preferred over parenteral nutrition. Similarly, enteral nutrition uses a technique of avoiding the stomach for digestion. Nasojejunal tubes pass through the nostrils and into the GI tract, bypassing the stomach and injecting food directly into the jejunum, or the part of the small intestines that absorbs sugars, amino acids and fatty acids. Enteral nutrition is indicated for severe weight loss (more than 5-10% in 3-6 months), recurrent hospitalization, and significant complications like diabetic ketoacidosis or poor quality of life (Achong et al., 2011).

Medical therapy focuses on prokinetics (aid in motility) and anti-emetics (avoid vomiting). Medications include erythromycin, metoclopramide, domperidone and cisapride. Surgical intervention with completion or subtotal gastrectomy is usually reserved for gastroparesis postvagotomy.

Gastric electrical stimulation via an implantable device has been used for patients with refractory symptoms. The exact mechanism of its beneficial effects is unknown but myoelectric modulation, sympathovagal activity modification, and thalamic effects have been theorized. However, there are no studies available with its use in the pregnant population (Achong et al., 2011).

Another part of the comprehensive plan is asking help whenever necessary. Hiring a doula during the pregnancy and after childbirth can help relieve stress, which can often trigger symptoms of gastroparesis. Consulting with a nutrition specialist can also help narrow down food choices that are both good for the mother and the baby.

Lifestyle changes are also very important. Drinking plenty of fluids including juice, broth, and low-fat soup throughout the day can help the stomach process solid foods and pass it on to the small intestines. Also, avoiding lying down for 4-5 hours or taking a gentle walk after eating can help take advantage of gravity to facilitate gastric emptying and also prevent acid reflux and other gastroparesis symptoms.

Final Thoughts

There is still no cure for gastroparesis given the difficulty of determining the exact cause of the disorder. However, lifestyle changes and medications can alleviate some of the symptoms.

Gastroparesis during pregnancy remains to be a difficult problem to manage. Pregnant women with the disorder must ensure that they have a comprehensive system for managing the symptoms of the disorder while maintaining a healthy lifestyle to take care of their mind and body, both for themselves and the baby.

References

- Achong, N., Fagermo, N., Scott, K., & D’emden, M. (2011). Gastroparesis in pregnancy: Case report and literature review. Obstetric Medicine 4(1), 30-34. doi: 10.1258/om.2010.100044

- Fuglsang, J., & Ovesen, P. (2015). Pregnancy and delivery in a woman with type 1 diabetes, gastroparesis, and a gastric neurostimulator. Diabetes Care 38(5), 75. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-2959