Cheese is considered generally safe and nutritious. However, food borne illnesses have also been linked to its consumption in many countries (Choi et al., 2016).

Among the many various types of cheese, hard cheeses are considered safe to consume during pregnancy. This includes parmesan cheese; Its low moisture content blocks the ability for bacteria like Listeria to thrive and cause an infection.

Benefits of Eating Cheese

Cheese is a mainstream food in numerous nations as a result of the related medical advantages and its flavor. The health advantages of cheese include natural probiotic and anti-tumor properties. Furthermore, cheese is a rich dietary source of calcium, phosphorus, and proteins, and has been shown to decrease the incidence of type II diabetes (Choi et al., 2016).

Two studies investigated the relationship between cheese intake and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. One study concluded that daily cheese consumption was found to lower the odds of osteoporosis, compared to no cheese consumption. Meanwhile, the other study showed that daily cheese consumption of more than 30 grams per day was associated with reduced odds of osteoporosis when compared with lower amounts of consumption in Iranian women, but not in Indian women (Ong et al., 2020).

In 2014, Hu et al. published a meta-analysis, which included results from 15 prospective cohort studies. It revealed that intake of low-fat dairy, fermented milk and cheese was significantly associated with decreased risk of stroke.

The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend a healthy eating pattern that includes milk, yogurt, and cheese. However, because a lot of cheese contains more sodium and saturated fats, the guidelines point out that higher intake of dairy products would be most beneficial if more fat-free or low-fat milk products were selected in exchange for cheese.

Food-Borne Diseases from Cheese Consumption

Cheese-related food borne diseases have been generally associated with consumption of soft cheese or other cheese made from raw and unpasteurized milk. Rarely were there occurrences of pathogenic illness linked to hard cheese (Choi et al., 2016).

Listeria Monocytogenes

Some types of cheese contain more moisture than others, and are an ideal environment for bacteria to grow in. Infection with Listeria monocytogenes is particularly harmful in pregnancy. It can lead to miscarriage, still birth or severe illness in a newborn infant.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), L. monocytogenes is widespread in the environment and can be introduced into a food processing facility. Foods can be contaminated if ingredients were not treated to destroy viable cells of this pathogen, or because of unsanitary conditions and practices.

Soft cheese has a high moisture content of more than 50% or 67% on a fat-free basis. This has been implicated as to why L. monocytogenes was often found in soft cheese. Moreover, this finding reveals that cheese may, in fact, represent a danger to consumers (Choi et al., 2016).

L. monocytogenes outbreaks that were related to consumption of cheese had a relatively high fatality rate of 15 to 30 percent. In 2005, ten cases of Listeriosis occurred in a northwestern Swiss town, of which two were pregnant women that developed a miscarriage during the infection (Choi et al., 2016). Around 25% of invasive Listeriosis cases were found to occur in pregnant women (Wing & Gregory, 2002).

Staphylococcus Aureus

Despite the fact that cheese is generally viewed as safe for human consumption, 0.4% of all food borne outbreaks has been associated with contaminated cheese in 2006 in the European Union. A large number of these food borne illnesses were a result of contamination with Staphylococcus aureus, which frequently causes mastitis in cows, leading to milk contamination (Choi et al., 2016).

In 2010, S. aureus was isolated from unpasteurized soft cheese for sale in California, which was found to be smuggled from Mexico into the US. Common reasons for pathogenic bacterial contamination in soft cheese include its high water activity and low acidity, as well as poor sanitation during the cheese-making process (Choi et al., 2016).

Salmonella

Different Salmonella serotypes have been implicated in food borne outbreaks associated with cheese. From March 2006 to April 2007, 85 individuals were affected by an outbreak of Salmonella from consumption of Mexican-style cheese in Illinois. In 2013, a multi-state Salmonella outbreak, which affected California (15 cases), Nevada (1 case) and Wyoming (1 case), has been linked to raw cashew cheese intake (Choi et al., 2016).

Types of Cheese and Safety During Pregnancy

Soft Cheese

Food borne illnesses that are associated with cheese have been attributed to consumption of soft cheese (Choi et al., 2016). In 2003, the FDA, together with the Food Safety and Inspection Service of the United States, released a risk assessment that estimated the risk of Listeriosis among different food categories. Foods that were listed as having the highest risk for Listeria proliferation include milk, butter and cream, and soft, unripened cheeses with greater than 50% moisture like cottage and ricotta cheese (US FDA, 2008).

Some soft cheeses are safe to eat for pregnant women as long as they were made from pasteurized milk. These include:

- Cottage cheese

- Mozzarella

- Feta

- Cream cheese

- Paneer

- Ricotta

- Halloumi

- Goats’ cheese

- Cheese spreads

Mold-ripened cheeses are those with a white rind. These include brie, camembert, and chevre. This type of cheese can only be safe for pregnant women if they were cooked prior to eating.

Soft blue cheeses are also considered safe if they have been cooked. These include Danish blue, gorgonzola, and Roquefort.

Learn More: Is Blue Cheese Safe to Consume During Pregnancy?

Hard Cheese

Hard cheeses are safe to eat during pregnancy. These include cheddar, parmesan, and stilton. Even if they were made from unpasteurized milk, their water content is very low, such that bacteria are less likely to grow.

The FDA compliance policy guide states that “Listeria monocytogenes does not grow when the water activity of the food is less than or equal to 0.92.” They listed foods that pose the lowest risk of causing Listeriosis, which include ice cream and frozen dairy products, cultured milk products like yogurt, sour cream and buttermilk, and hard cheeses with less than 39% moisture like cheddar, colby and parmesan cheese (US FDA, 2008).

Parmesan Cheese

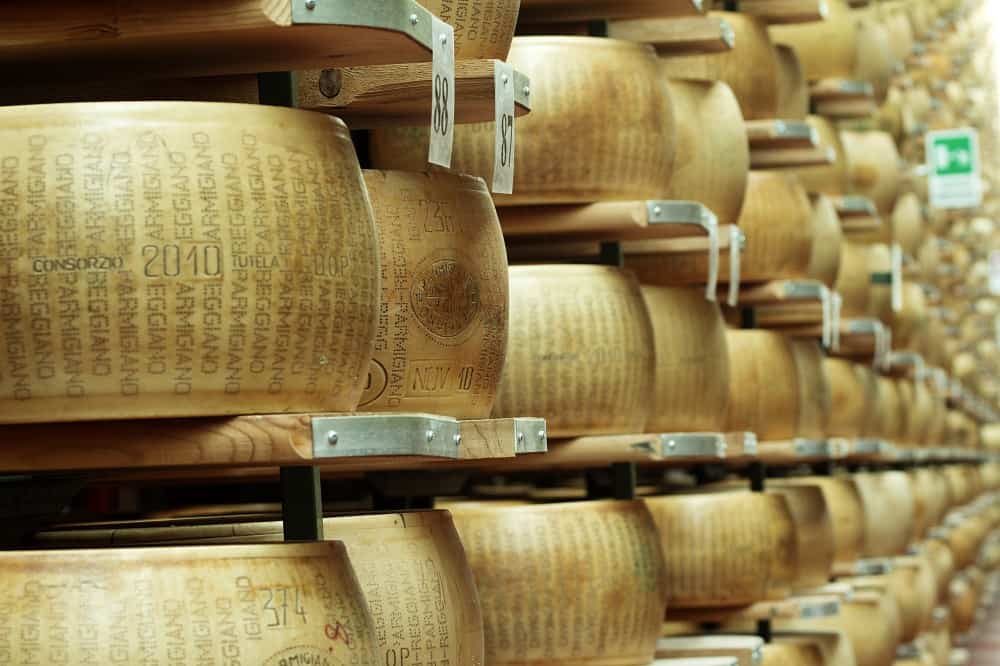

Parmigiano Reggiano

Parmigiano Reggiano is the classic parmesan cheese. It is an extra hard cheese with a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), meaning that it can only be produced in a specific geographical area in Italy using the traditional recipe described in the product specification (D’Incecco et al., 2020).

The origin of this artisanal cheese dates back to 1200-1300 A.C. Hence, its production technology has developed for more than 700 years of history. In its production area, cattle are fed on locally grown forage, and use of silage and fermented feeds is not allowed (Neviani et al., 2013).

It is made from raw, unpasteurized milk, and the minimum ripening period is 12 months. However, it can also be aged for much longer. D’Incecco et al. (2020) investigated the effects of ripening Parmigiano Reggiano for 50 months. They found that longer aging increased the cheese hardness, as well as constantly decreased its moisture until it was only 25%.

Generic Parmesan

Generic parmesan cheeses are common in the US and other countries outside Europe. They can be made with either pasteurized or unpasteurized milk. Their quality can vary greatly, as there are many dairy farms that strive to make delicious parmesan, while there are also a lot of mass-produced parmesan wedges that are less flavorful.

The word “parmesan” is derived from Parmigiano. Generic parmesan cheese has basic ingredients the same as in Parmigiano Reggiano: cow’s milk, salt and rennet. Its production and aging process are, likewise, not any different.

Pre-grated parmesan cheese is available in many supermarkets. However, this cannot be compared with freshly grated cheese. Domestic and imported generic parmesan cheese are also being sold in specialty cheese stores and Italian markets.

Is Parmesan Cheese Safe for Pregnant Women?

The low moisture content in parmesan cheese makes it very difficult for bacterial pathogens like Listeria to survive and grow in it. Therefore, it is considered safe for consumption during pregnancy.

The longer the aging of parmesan cheese, the less water content it has and the less risk there is for Listeria and other pathogens to thrive. Thus, older parmesan cheeses are even safer for pregnant women.

In the United States, all generic parmesan cheeses made from unpasteurized milk are required by law to be aged for more than 2 months. This makes them highly unlikely for Listeria to survive. The US FDA (2008) lists parmesan cheese as food that “does not support the growth” of Listeria.

Back in 1990, Yousef & Marth made a study to deliberately inoculate Listeria monocytogenes and investigate its survival during the production of parmesan cheese. They found that the maximum quantity of L. monocytogenes appeared just before cooking. During the aging process, numbers of Listeria decreased dramatically, until after 2 to 16 weeks, when there was no more Listeria detectable in the cheese.

Because of the hard texture and low moisture content in parmesan cheese, it can be safely consumed by pregnant women even when cold, uncooked or sliced straight from the packet.

Final Thoughts

As cheese consumption has been linked to both health benefits and potential dangers, it is important to know which types are safe, especially during pregnancy. Hard cheeses like parmesan cheese contain low water and moisture, no matter if they were made from pasteurized or unpasteurized cow’s milk. Therefore, they are considered safe to eat by pregnant women.

Dairy products are part of a nutritious, balanced diet during pregnancy. But over and over, it must be emphasized that a health care consultation is best when pregnant women find themselves faced with making unsure dietary decisions.

References

- https://111.wales.nhs.uk/livewell/

- https://www.thespruceeats.com/

- https://www.treehugger.com/

- Choi, K., Lee, H., Lee, S., Kim, S., & Yoon, Y. (2016). Cheese microbial risk assessments: A review. Asian- Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 29(3), 307-314. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0332

- D’Incecco, P., Limbo, S., Hogenboom, J., Rosi, V., Gobbi, S., & Pellegrino, L. (2020). Impact of extending hard-cheese ripening: A multiparameter characterization of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese ripened up to 50 months. Foods 9(3), 268. doi: 10.3390/foods9030268

- Hu, D., Huang, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, D., & Qu, Y. (2014). Dairy foods and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 24(5), 460-469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2013.12.006

- Neviani, E., Bottari, B., Lazzi, C., & Gatti, M. (2013). New developments in the study of the microbiota of raw-milk, long-ripened cheeses by molecular methods: The case of Grana Padano and Parmigiano Reggiano. Frontiers in Microbiology 4, 36. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00036

- Ong, A., Kang, K., Wiler, H., & Morin, S. (2020). Fermented milk products and bone health in postmenopausal women: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials, prospective cohorts, and case-control studies. Advances in Nutrition 11(2), 251-265. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz108

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). 2015-2020 dietary guidelines for Americans: 8th edition. Retrieved from https://health.gov/our-work/food- nutrition/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2008). Compliance policy guide (CPG): CPG Sec 555.320 Listeria monocytogenes. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda- guidance-documents/cpg-sec-555320-listeria-monocytogenes#IV_B

- Wing, E., & Gregory, S. (2002). Listeria monocytogenes: Clinical and experimental update. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 185(Suppl 1), S18-24. doi: 10.1086/338465

- Yousef, A. E., & Marth, E. H. (1990). Fate of Listeria monocytogenes during the manufacture and ripening of parmesan cheese. Journal of Dairy Science 73(12), 3351-3356. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022- 0302(90)79030-3